In 2001, Mark Wagner, AIA, found himself overlooking the rubble of destruction after two airplanes struck the Twin Towers at the World Trade Center one week after September 11. Fulfilling a request by the chief architect of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to describe what was left of their offices in the North Tower, and what might be salvageable, Wagner sent back a memo that changed his life for the next 13 years.

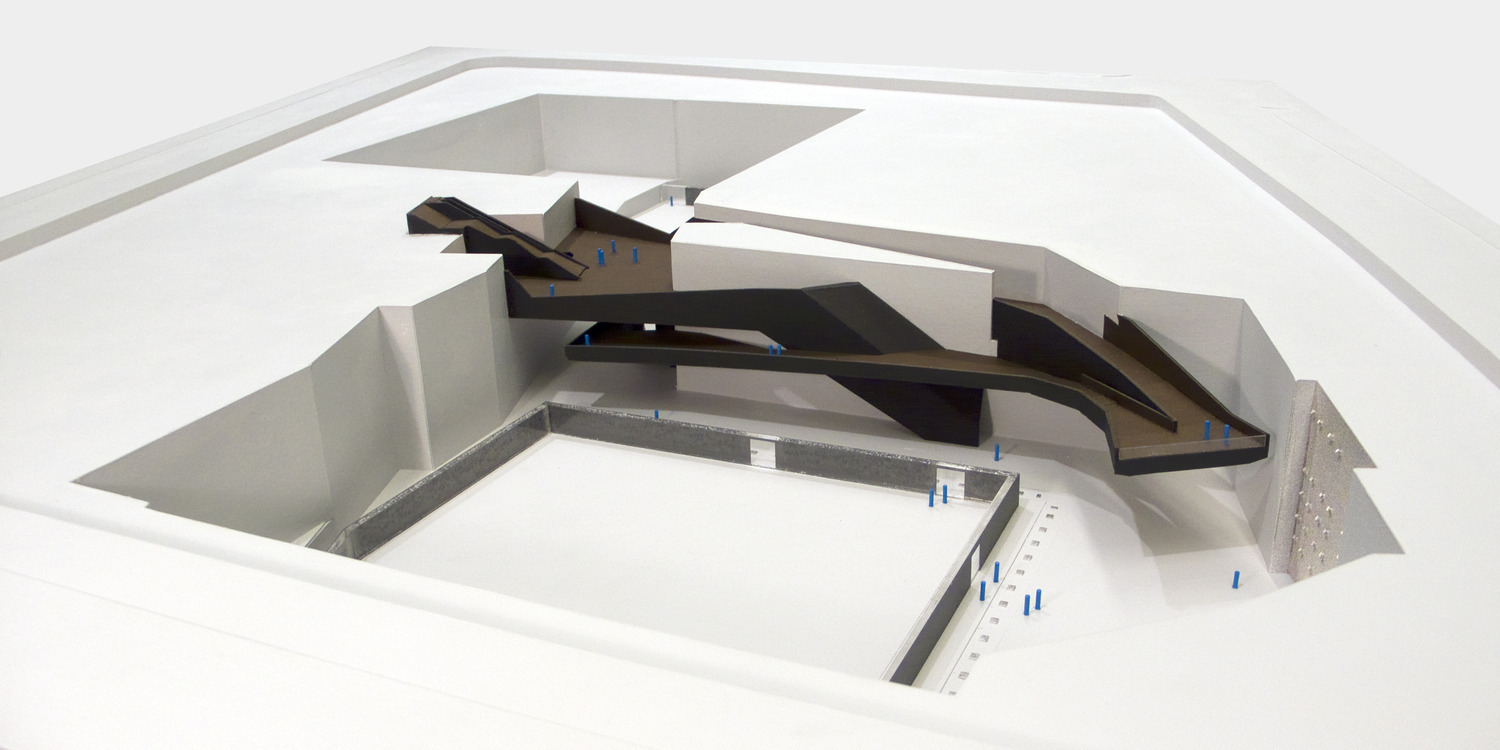

Following that memo, Wagner spent the next eight months sifting through what was left of the Twin Towers at Ground Zero, carefully selecting and archiving over 1,000 pieces that he and other workers at Ground Zero thought were reflective of the cultural memory of the Twin Towers, storing those pieces at an unused airplane hangar at JFK Airport. When Davis Brody Bond was commissioned to design the 9/11 Memorial Museum, Wagner’s unique experience and deep understanding of the site helped inform the concept of the museum.

However, Wagner is quick to clarify that the 9/11 Museum “was never our building.” Instead, its creation was driven by a deeper purpose: to resonate with those who lost loved ones and to honor the sacrifices of firefighters, first responders, and cleanup crews. The 9/11 Museum serves as a testament to their bravery and resilience, highlighting New York’s strength and reinforcing a global truth: we all need to support each other.

For the past ten years since its opening, the 9/11 Museum has served as a living memorial, and as we look to the future, it continues to be a space where the collective memory of these events is preserved and shared. It stands not merely as a building but as a beacon of remembrance and unity, ensuring that the lessons and legacies of that fateful day continue to inspire and connect us all.

The 9/11 Museum in lower Manhattan now embodies a compelling fusion of soft power, urban revitalization, and the transformative impact of cultural institutions beyond their physical boundaries. As a symbol of remembrance and resilience, the museum not only honors the profound events of September 11 but also plays a pivotal role in rejuvenating the surrounding area. By drawing millions of visitors each year, the museum has become a catalyst for economic growth and cultural enrichment, infusing new vitality into a historically financial district. Its influence extends far beyond its walls, shaping public discourse and fostering a deeper understanding of global events. Through thoughtful programming and impactful exhibitions, the 9/11 Museum demonstrates how museums can serve as agents of change, using their unique soft power to inspire reflection, dialogue, and renewal in both the local community and the wider world.

Here’s a continuation of our wide-ranging conversation from two weeks ago.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Page:

I’m wondering, how do you now digest the museum’s power to bring so many different people together?

Mark Wagner:

While I don't mean to diminish the significance of the 9/11 Museum or its architecture, I believe the power comes from the site and the event itself.

In the weeks following 9/11, people traveled from all over the world just to stand on the perimeter of the site, even though you couldn’t see anything in that area and the secure perimeter was a few blocks away. Despite not being able to see much, people felt a compelling need to be there—to witness it for themselves, to be part of something significant, and to show their respect and support. They had to see it for themselves, or they wouldn’t be able to believe it. There were hundreds of tasks going on around the site. People were holding signs on the perimeter just for support, others were helping with artifact selection, or performing various jobs like debris removal, and the architecture and the site’s inherent power drew them in. People wanted to help in any way they could, physically and emotionally. Even if we had left a hole in the ground, it would still hold that powerful significance.

The architecture needed to recognize that power and be true to that authenticity in some way. Not build a building that was so far removed. It couldn’t be physically removed from the site, but although that was suggested at some point, to move the location of the museum. People questioned it - why are you building it there? In my opinion, it had to be there, physically. It had to acknowledge that power of the site.

In our New York office, where we frequently work with historic and cultural projects, we follow a common philosophy: we strive to understand a site's or building's past to better address the building or the current needs. The buildings often have a different kind of meaning, but we do like to understand the past, so we can somehow understand what that is going to be in the future.

In this case, the past of the World Trade Center obviously includes the events of 9/11, but it was also the cultural memory that New Yorkers held for the place. You see the Twin Towers everywhere in pop culture, or at least I see them everywhere in movies and television programs. They’re everywhere. The WTC was always part of our DNA in some way, and we didn't really realize it. When New York was talked about or included in a film, the Trade Center was always part of that visual. That was New York.

That understanding of the site's significance—both before and after 9/11—was central to driving the architecture. Equally important was considering what the site's significance might mean for future generations who may not have the same connection to it. The architecture had to address and confront this authenticity, and that authenticity is simultaneously joyous and horrific. Ultimately, the architecture had to remain true to the place.

Page:

What was the lesson or lessons learned from this project that you carry forward now? Is there a lesson or two that you learned as an architect in 2001 that still holds true in 2024?

Wagner:

It really has formed and informed my philosophy and my approach to architecture.

I believe architecture goes beyond merely addressing the immediate program or needs of a project. It also involves understanding the place’s history and how that history impacts and informs the design of current and future uses. A building should not only fulfill its intended purpose but also anticipate future needs. All three aspects—historical context, current requirements, and future potential—are crucial. Additionally, I’ve learned and now put into my general philosophy that a building’s impact extends beyond its physical walls, influencing and interacting with its broader environment.

What I learned from it and carried through to almost every project now is the understanding that buildings or sites have a past history, they have a current existence, and they have a future coming to them. So, stringing those things together and understanding how they work and support each other is critical. I enjoy working on this type of architecture - this idea of projects that are never just about a building itself, but how that building will impact and influence the surrounding community.

Ideally, when you visit the 9/11 Museum, you come away with new insights, particularly the lesson that we can strive to be better toward one another. As you leave the museum and return to the world, I hope you carry that sense of understanding and compassion with you. But the idea that a building, the program, and the influence of that building and program stop at the front door, and it's all contained within that building? That doesn't ring true to me anymore.

A building impacts its community. It reforms the activity and the life around that building, both in a direct and an indirect way. The building's attitude can really change a location. If we think about lower Manhattan and the redevelopment of the Trade Center site, before 9/11 lower Manhattan went from being this very business-dominant financial hub of the world, and perhaps now is a cultural center of the world too. And that changes the local economy. That changes everything around there; the businesses and the shops, and the support spaces that have popped up. It's all different now and it just takes on a new life. The short summary is our buildings are never just about our buildings. Our buildings are about the impact that they make on our culture, our community, and the society around them.

Page:

As someone who isn’t familiar with Manhattan, can you explain what has changed in lower Manhattan in terms of businesses and how it is different now?

Wagner:

It's not just the 9/11 Museum that contributed to that change. The master plan introduced the Memorial & Museum, and it introduced the Perelman Performing Arts Center, which Davis Brody Bond (a Page Company) was also involved in. [Editor’s note: Studio Daniel Libeskind was selected to develop the master plan for the site in 2003. His framework, or footprint was used as a guide to capture the memory of the site.]

In this scenario, cultural institutions often attract other cultural entities, creating a synergistic effect where institutions benefit from each other's success and mission. Since 9/11, several other museums, such as The Museum of Jewish Heritage and the National Museum of the American Indian, have benefited from the additional visitors to lower Manhattan, enhancing its prominence as a cultural hub. While lower Manhattan has always been rich in cultural significance, visitors previously came primarily for landmarks like the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. Then people would realize they could visit other important American historical sites such as Castle Clinton National Monument and Fraunces Tavern. But that wasn’t what got you there in the first place.

The Statue of Liberty has always been a major attraction too, and now the 9/11 Museum has become another significant draw. This increase in tourism is transforming the local economy and diversifying the types of people who visit the area. Before 9/11, as a born-and-raised New Yorker, I could count on two hands the number of times I visited the financial district. It was primarily a business hub that emptied out after 5:00 PM, with few options for dining because the lunch spots would close. Today, however, the area is bustling with a vibrant mix of hotels, restaurants, and music venues, bringing new life to the neighborhood.

Different things have all started to happen now. That's not all triggered by the 9/11 Museum landing there, but it is triggered by a collaborative interest in changing the economy of that area.

Page:

It sounds like the architecture reflects the way people want to experience history, where it happens. Not miles away.

Wagner:

Absolutely. In some of the talks that I’ve been involved in, we've been exploring how many institutions traditionally viewed themselves as primarily for visitors and tourists. Often, people would visit a museum once or twice in their lifetime and see no compelling reason to return. So, how do we promote and really push museums to become part of a vital, evolving, recurring cultural experience for the locals? The goal is to make museums integral to the local cultural experience, encouraging repeat visits not just for the museum's financial stability, but for the cultural enrichment of the community. By offering changing exhibits and engaging programs, museums can motivate visitors to return, whether it's this summer or in six months, to experience something new and relevant.

And then also, our conversations focus on how we want visitors to think and engage with their museum experience. It’s not just about viewing art or exhibits; we aim to spark discussions and intellectual conversations, both inside and outside the museum, about what people have seen. We want that attitude and those conversations to continue. It swings back to the idea that a building is never really about the four walls that contain the program. The goal is to extend the impact of the museum experience beyond its walls, encouraging ongoing dialogue and reflection. A building is more than just the physical space that houses its programs; it's about how those programs resonate in our minds and continue to inspire conversations. Museums should evolve and provoke thought, remaining relevant not only for this generation but for future ones as well.

Jennifer Wegner, a contributor to this story, is the Editorial Manager at Page.