Electromagnetic (EM) fields—generated by everything from power lines to smartphones—are an invisible but pervasive aspect of the modern world. While these frequencies enable countless wireless devices, they can also pose significant challenges for inclusive design by interfering with hearing aids and cochlear implants.

Cochlear implants, for instance, rely on the delicate interplay of an external processor and an internal receiver, connected through electromagnetic energy, to enable real-time sound processing. Hearing aids similarly use low-frequency bands to enable wireless communication and adaptive listening. However, when devices in the environment emit overlapping frequencies, electromagnetic interference (EMI) can disrupt these critical assistive technologies, compromising their effectiveness.

The need for reliable assistive technology is vast. As of July 2022, more than 1 million cochlear implants have been implanted worldwide. In the United States alone, 7% of adults currently use hearing aids, though 28.8 million adults could benefit from them.1,2 This reliance on assistive devices underscores the importance of environments that support their functionality.

At Page, inclusive design isn’t just about addressing the minimum accessibility standards; it’s about creating environments where assistive technologies are uninterrupted and uncompromised. This philosophy drives our ultra-inclusive design approach, expanding the concept of sensory-friendly spaces to address the complex challenges of EMI in real-world applications.

Data-Driven Mapping: Understanding the Invisible Threat of EMI

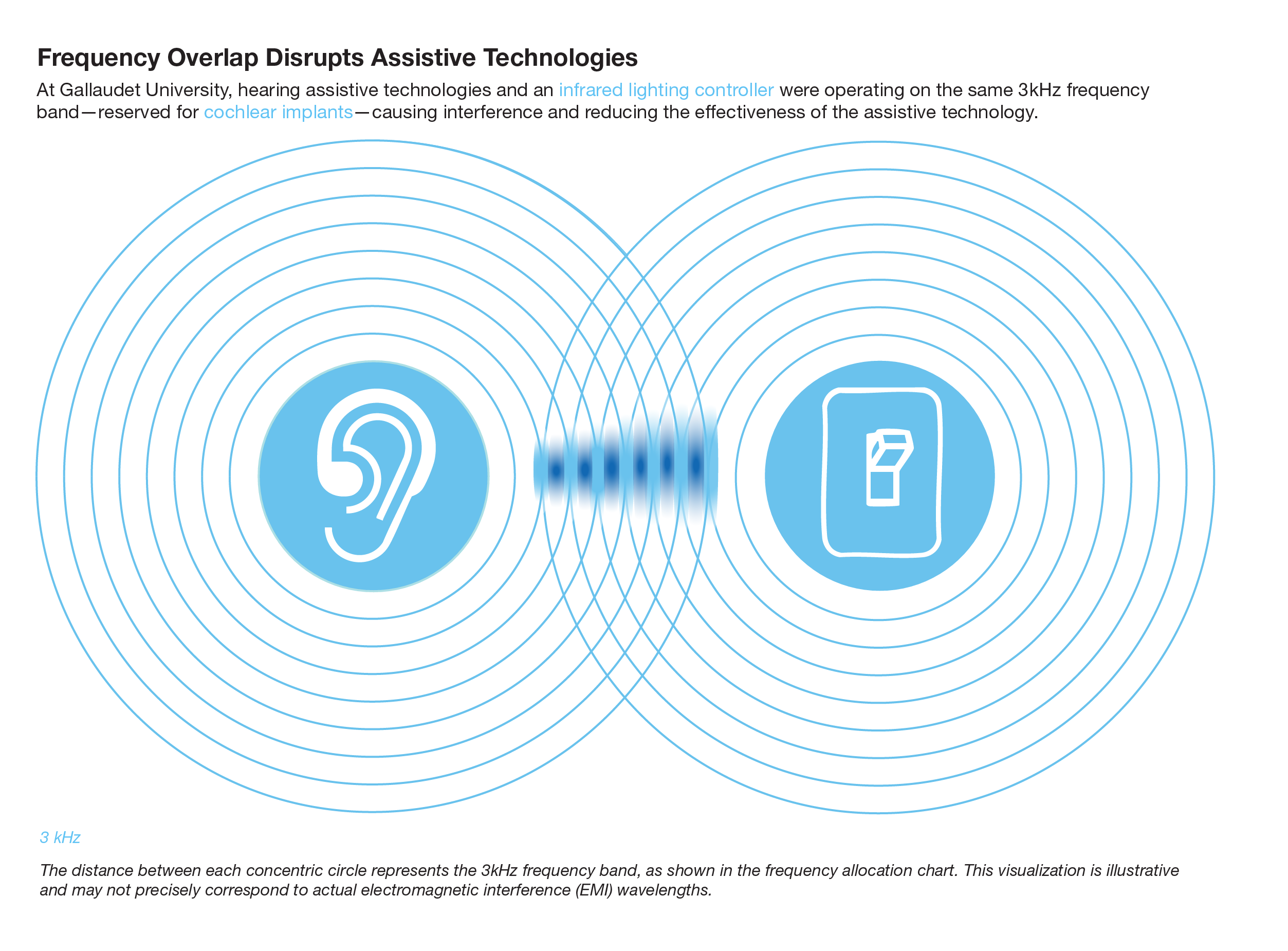

Gallaudet University, a global leader in education for the Deaf and hard of hearing, presented a compelling case of electromagnetic interference (EMI) disrupting assistive technology. As Hansel Bauman, former Gallaudet Campus Architect and co-author of the Gallaudet University DeafSpace Design Guidelines said, “We understand how disruptive EMI can be but are perplexed by the cause of disruption at localized areas on campus where hearing aids and cochlear implants always fail, creating significant challenges for many of our students and faculty.”

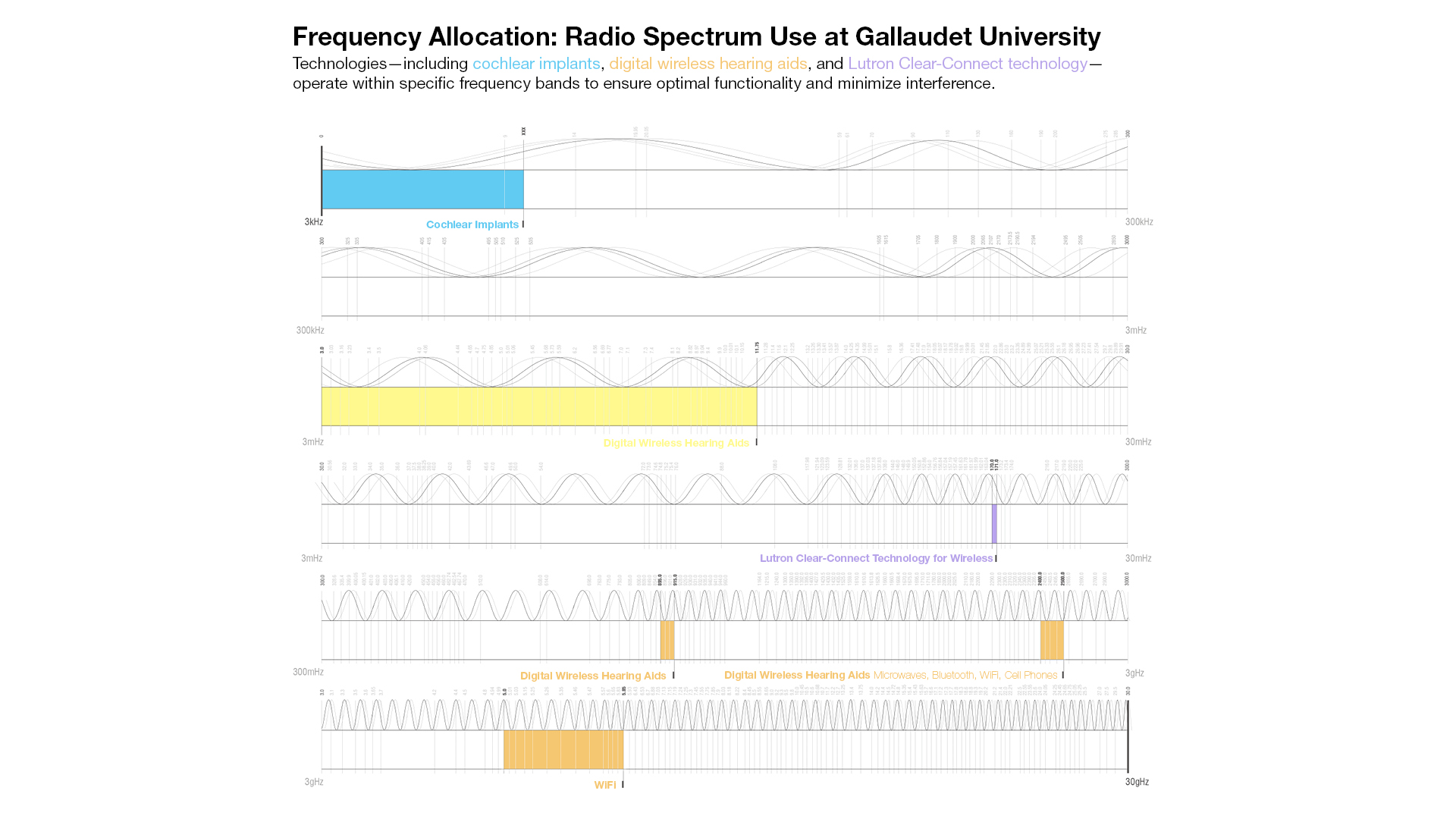

Prior to designing and building a new space for Gallaudet, we addressed this ever-present interruption of listening devices to improve the overall student experience in campus environments. Partnering with Interface Engineering, Page conducted a detailed investigation, including electromagnetic spectrum mapping. Using annotated frequency allocation maps from the U.S. Department of Commerce, we identified the root cause: an infrared lighting controller, integrated during the building’s construction, that emitted frequencies that overlapped with those of assistive devices.3 This interference rendered devices temporarily inoperative when users approached these systems.

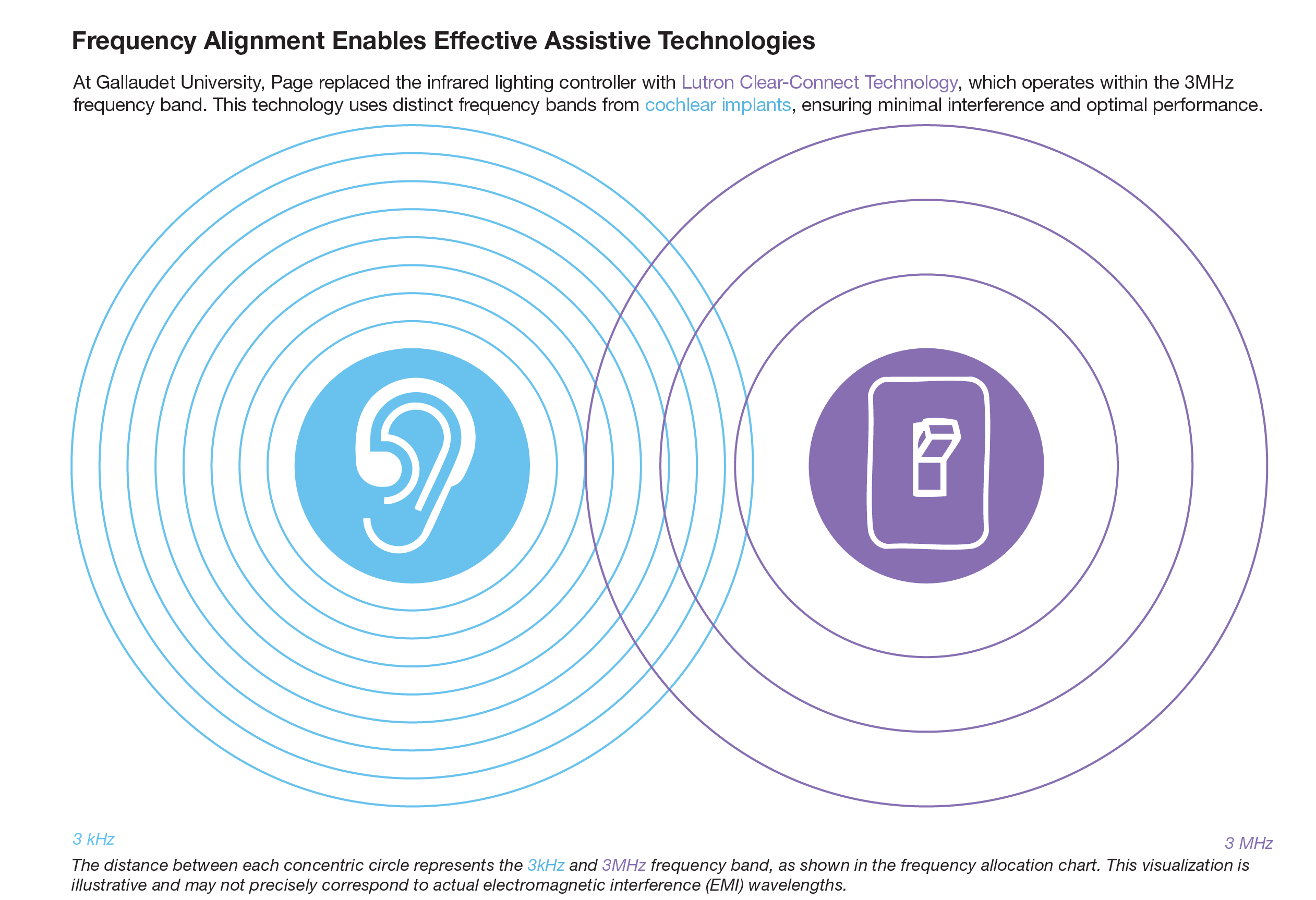

Guided by spectrum analysis, we implemented a targeted solution—replacing the lighting controller with Lutron Clear-Connect Technology, a device operating on non-interfering frequencies. This intervention restored seamless functionality for assistive technologies, ensuring an accessible and reliable environment. The impact of this singular device highlights the profound implications of unintentional EMI in built environments.

Solving Electromagnetic Interference

Shielding Solutions: Practical Interventions in Architectural Design

Creating environments that support seamless functionality for hearing aid and cochlear implant users requires a multi-faceted approach grounded in rigorous research and technical innovation.

By addressing electromagnetic interference (EMI) at the architectural level, designers and engineers can ensure that assistive technologies remain reliable and effective. The following strategies, supported by research and case studies, outline practical interventions to mitigate EMI in modern facilities:

1. Data-Driven Frequency Mapping:

A foundational step in addressing EMI is conducting a comprehensive electromagnetic spectrum analysis within a given environment. Using advanced tools such as spectrum analyzers, designers can measure signal strength, frequency distribution, and potential interference zones. This process allows for the identification of high-risk overlap areas, particularly those where assistive technologies may conflict with other devices operating on similar frequency bands.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and related agencies, such as the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) and the Office of Spectrum Management, regulate the radio frequency spectrum in the United States. The FCC highlights specific frequency bands reserved for devices – for example, 72–76 MHz, 216–217 MHz, and 2.4 GHz are dedicated for Bluetooth technologies.

Studies have shown that EMI can significantly disrupt cochlear implants when external devices emit overlapping frequencies, particularly within the 2–500 MHz range, a band often occupied by common environmental sources such as lighting systems or mobile devices.4

Comparing real-time data with these allocations enables the creation of targeted interventions to minimize disruptions.

1. Shielding and Isolation Strategies:

The materials and construction techniques used in a building’s infrastructure can significantly influence EMI propagation. Technologies such as frequency-absorbing coatings, embedded mesh barriers, and layered shielding provide powerful tools to control signal propagation while maintaining architectural integrity.

· RF-Absorbing Coatings: Paints and films infused with conductive particles can attenuate unwanted signals by absorbing rather than reflecting electromagnetic waves.

· Embedded Mesh Barriers: Conductive meshes within walls and windows can act as Faraday cages, selectively blocking high-risk frequencies while allowing essential signals to pass through. This approach has been particularly effective in retrofitting historic buildings, where structural changes may be limited.

· Layered Shielding: Multi-layered wall systems incorporating conductive materials and insulation can create zones of controlled signal propagation.

These interventions are designed not only to mitigate EMI but also to maintain the aesthetic and functional integrity of the architectural design. For example, transparent shielding films for windows preserve natural light while providing electromagnetic protection.

3. Spatial Adjacency Optimization:

The physical layout of wireless systems and user spaces plays a critical role in managing EMI. Proximity to high-density wireless zones—such as server rooms, Wi-Fi hubs, or 5G transmitters—can amplify interference risks for assistive technologies. To address this, spatial adjacency optimization involves:

· Strategically placing spaces where assistive listening is frequently required, such as theaters, conference rooms, or classrooms, away from wireless infrastructure.

· Creating physical buffers or shielded zones between high-EMI areas and user-centric spaces. For example, placing storage rooms or utility spaces between a server room and a lecture hall can act as a barrier.

· Designing flexible layouts that allow for future technology upgrades, ensuring that EMI mitigation strategies remain effective as wireless technologies evolve.

The intersection of wireless innovation and assistive technology calls for a forward-thinking approach to inclusivity. By leveraging tools like frequency mapping, advanced shielding materials, and spatial adjacencies, we can anticipate challenges before they arise, ensuring environments are not just compliant but aspirational in their inclusivity.

At Page, we aim to set a new benchmark for designing spaces where technology empowers everyone, proving that innovation and accessibility can—and must—go hand in hand.

References:

1. Quick Statistics About Hearing, Balance, & Dizziness. (September 20, 2024.) National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Available at: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing#13

2. Focareta, D. Hearing aid statistics 2025. (March 26, 2024.) Journal of Consumer Research. Available at: https://www.consumeraffairs.com/health/hearing-aid-statistics.html#:~:t….

3. United States Frequency Allocation Chart. (January 2016.) National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Available at: https://www.ntia.gov/page/united-states-frequency-allocation-chart

4. Tognola, G., et al. Electromagnetic interference and cochlear implants. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2007;43(3): 241-247.