On the morning of September 11, 2001, Mark Wagner, AIA, was running late to a meeting with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey on the 72nd floor of the World Trade Center’s North Tower. He had stopped by his employer’s office in midtown to grab some architectural drawings he had forgotten. On his way out the door, the porter of the office building stopped him, saying “You might not want to go the WTC right now, something’s going on.” Wagner returned to his office, staying to watch the news unfold on television a safe distance from the WTC. A week later, Wagner was contacted through his then-employer by the chief architect at the Port Authority to update him on what was left of their office; he couldn’t bear to go see for himself what was left of his home. That request set Wagner on a 13-year journey to preserve the cultural memory of the site, guiding the design of the 9/11 Museum through the principle concepts of witness, authenticity, and emotion. Wagner’s insights into memorial and museum architecture reveal a profound understanding of how these spaces resonate with visitors across generations.

A few weeks ago, Mr. Wagner and I shared a wide-ranging discussion on his approach to the preservation of artifacts for the 9/11 Museum, the complexities of planning memorials and museums, how modern museums can bridge generational gaps, and how memory and emotion in architecture are adapting to changing societal contexts and technological advancements through innovative design strategies.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Page:

There’s valuable historical insight to be gained from your experience with the 9/11 Museum, and I’m interested in your perspective on future trends in memorial and museum architecture.

Wagner:

I remember sitting on a panel in 2002 or 2003 to discuss the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C. To me, it's one of the most successful memorials in a very abstract way. The need to memorialize or the way we memorialize, I believe, hasn't evolved significantly over the past few centuries. Memorials come in various forms—there are monuments, memorials, and places of interpretation. The term "interpretation" can be tricky because we're not interpreting the event ourselves; rather, we're providing a platform for others to interpret it.

At the panel, we were discussing what was happening at the Vietnam Memorial. They realized that as people got farther and farther away from the war, they began to question whether the Vietnam Memorial still had the same impact on visitors who were so far removed from it. This idea that this wall with the names cut into the earth; does it still have the impact it did forty years ago? Memorials have common themes and we only have about five good ideas that go into all of them.

In a memorial, we all experience similar elements: names, a ceremonial procession, and a departure from everyday life that often involves water or a physical incision in the earth to focus our emotions and state of mind. As time passed and people became more distant from the war, it became clear that an interpretive center was needed—a place to tell the story, provide context, and establish a personal connection for those far removed from the event. The new generation may not have direct knowledge of the Vietnam War, so the challenge is to bridge that gap. We recognized this need in 2004 with the establishment of the 9/11 Museum. As generations pass, it's crucial to maintain a personal connection to historical events.

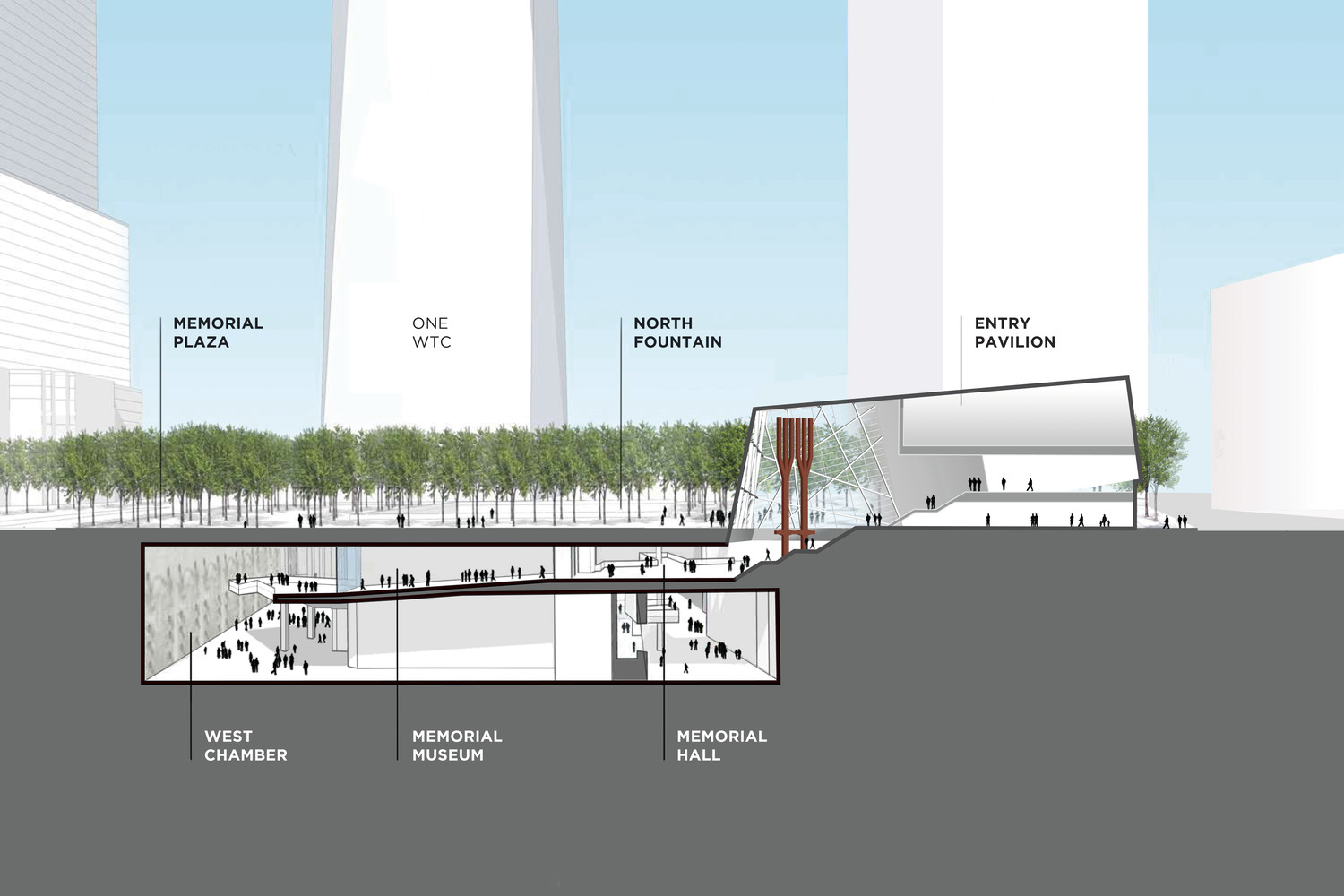

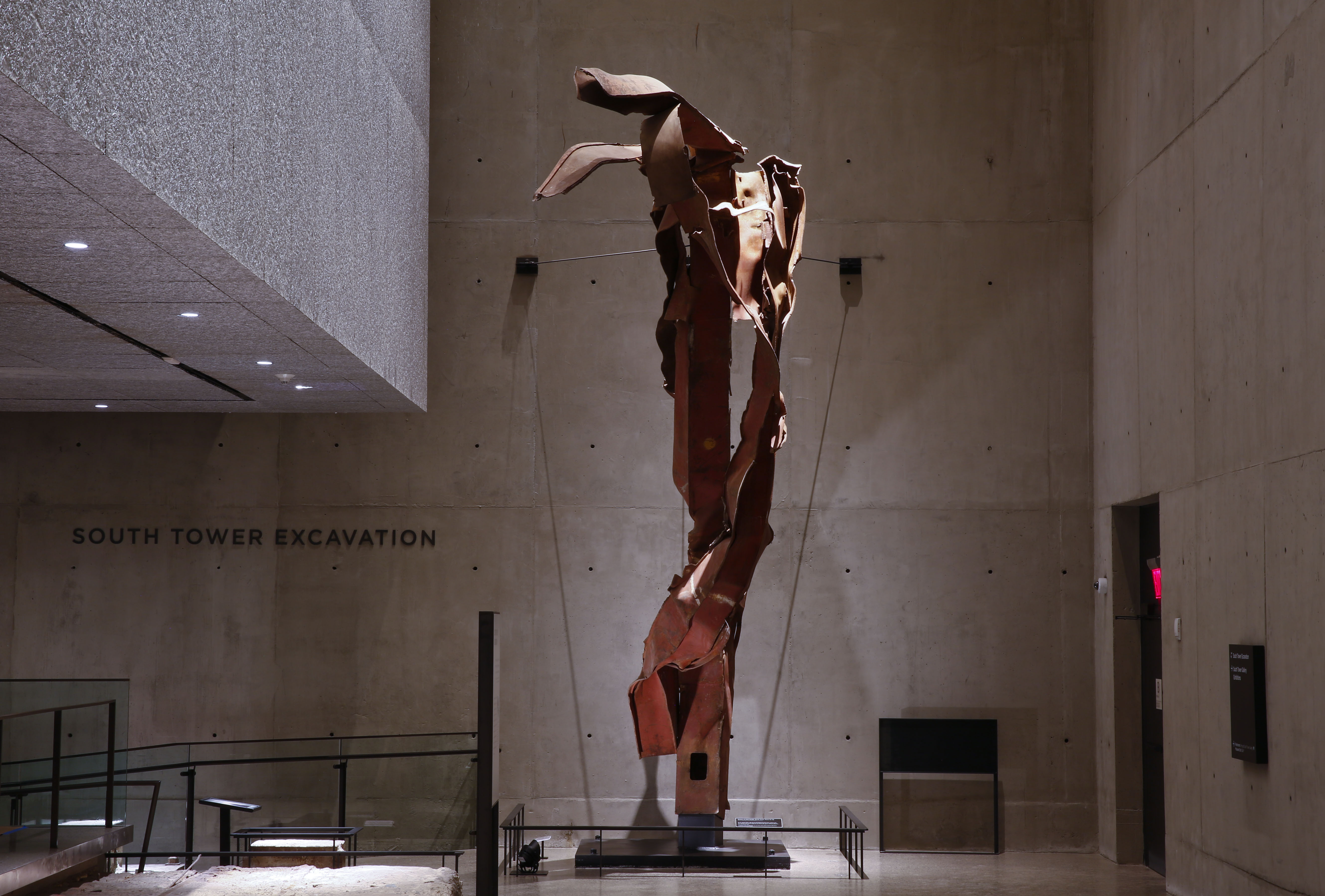

This is where our approach to memorial and museum design begins to evolve. The challenge becomes how to foster a personal connection and provide meaningful engagement. While the physical space of the 9/11 Memorial Museum will remain unchanged—such as the slurry wall, the tower footprints, and the ramp—the way we present and interact with the space is constantly developing. The large silver volumes, symbolic but not literal representations of the towers, will remain as they are. However, the technology and visitor interaction with the museum's interpretive content are continually advancing. With technology playing a larger role and younger generations growing up with digital devices and online learning tools, the method of presenting information is evolving. Despite these changes in presentation, the essence of the memorial museum, rooted in its connection to the earth and the authenticity of place, remains steadfast.

We use different methods or design strategies to change our state of mind for that moment and the 9/11 Memorial Museum is an extension in many ways of the Memorial. The Memorial on the plaza is very abstract with the two voids or pools representing loss. They're beautiful. They’re serene. The names circle around the parapets on all sides, but that abstraction needs some interpretation.

As you move into the 9/11 Museum, it then ties you to the authentic place through memory. Through these series of thresholds, it ties you to the physical remnants; the slurry wall and the footprints being the two biggest physical remnants. The tower volumes material we constructed are intentionally [hazy-like] and they are lit somewhat theatrically. They take on an ephemeral quality. In some ways you always see these tower volumes in the periphery whether you recognize them as an abstraction of the towers or not, they are always there. The towers were always there, and they became ephemeral in a way like our memories are. Memories sort of fade. These towers and our memory of the towers fade and transition to a new generation. I think the things to look for in those trends are how can we use modern technology, whether that be digital technology or building materials, and how can we use what's on hand today to provide that platform so that people can form their own experience around it.

Memorials and monuments haven’t evolved significantly over time. Many still follow traditional forms. In small towns across America, you might find a traffic circle with a clock or a statue of a World War I soldier—those monuments often don't convey much of a story. Modern approaches to memorialization have moved beyond these static symbols and moved towards more storytelling. We now aim to create spaces that connect visitors more deeply with historical events, whether through immersive experiences, or evocative design.

Not all memorials are linked to tragedy; some celebrate uplifting moments in our history. Memorials serve various purposes, but as each generation interacts with them differently, connecting with events that are further in the past becomes more challenging. To address this, we need to rethink our design strategies and adapt our tools to engage future generations we haven’t met yet in ways we haven't imagined.

Page:

You’ve raised an intriguing point. As you were speaking, I was reminded of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. I recall visiting it when it first opened in 2004—it’s a substantial space, but it feels quite open and unfilled. Last year, I read about the National World War II Museum in New Orleans and began to think about the missed opportunity of not having the World War II Museum located near the World War II Memorial. Would it have been more impactful to combine these two elements in the same place? Should this kind of integration be considered for future memorials?

Wagner:

I think from my perspective it's an absolute need, if that’s physically possible. The example that you brought up about the National World War II Museum is particularly relevant. I was involved in the winning design competition when I was still at my other firm before joining Davis Brody Bond. I knew planning for the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. had begun. But the memorial was going to be built in D.C. and this museum was being constructed in New Orleans and we were questioning why is this museum here? Many people don't recognize why the National World War II Museum is in New Orleans and it has a very specific reason. [Editor’s note: The Higgins boats designed for troops’ amphibious landings to beaches were designed and made in New Orleans. Eisenhower was later quoted as saying those boats “won the war for us.”]

Before its renovation and expansion, the museum was known as the D-Day Museum and focused primarily on D-Day. Visiting it and meeting with veterans—who were docents—provided a deep, personal understanding of their experiences. This made the purpose of the memorial in D.C. clear to me. However, I’ve observed that for many people, especially those who are distanced from World War II, there’s often a disconnect between the memorial and the museum. I could see it on the faces of others who didn’t make that connection.

For those who may know only that their grandfather served in the war but lack a deeper understanding of what that really means, standing in the open space of the World War II Memorial, surrounded by columns and names, can feel abstract and impersonal. The meaningful impact of the memorial becomes apparent only when linked to real events and the history conveyed by the museum. This disconnect represents a significant missed opportunity. Nevertheless, I understand the reasoning behind having the National World War II Museum in New Orleans and the World War II Memorial in D.C.

For 9/11, it was crucial to integrate the memorial with a museum from the start. We recognized that the time to build the museum was now; we couldn’t afford to delay for ten years. This is a challenge the Vietnam Memorial faces—it was initially created without an interpretive center, and only later did they acknowledge the need for one to help connect visitors with the history of the Vietnam War.

The 9/11 Museum had the opportunity to develop both the memorial and the museum concurrently, allowing them to support and enhance each other. This simultaneous development is a significant success. The 9/11 Memorial benefits greatly from the presence of the 9/11 Museum, and vice versa. Together, they create a cohesive and impactful experience on the actual site of the event.

Page:

The two structures, the 9/11 Memorial and Museum, exemplify a symbiotic relationship, each enhancing the impact of the other. This makes me consider other museums dedicated to preserving the legacies of individuals affected by major cultural and political events in our country. The collective goal of these museums is to forge connections with future generations, ensuring that these important stories remain relevant and impactful.

Wagner:

Exactly, and the way we tell that story is crucial—how we highlight its cultural impact. For instance, World War II is an immense and complex narrative. I often reflect on my work in New Orleans for the National World War II Museum, a project I didn’t see through to completion because I transitioned to the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

Thinking back, there’s a point in adolescence when we start to grasp the significance of major wars. I first became aware of this during junior high, and the scale of these global events is overwhelming. The enormity of World War II, for example, is hard to fully comprehend as a child. My initial reaction was one of astonishment and curiosity—wanting to learn more. Despite having some historical background, it wasn’t until I conducted research for the National World War II Museum competition that I truly began to understand the depth of the stories and their impact.

For me, the essence of what 9/11 represents and what the 9/11 Museum conveys extends beyond just the collapse of the buildings or the attack itself. While the loss of life is central, the Museum also highlights the broader impact on the community and society. As you move through the museum, especially from the historical exhibits to the Foundation Hall, it emphasizes the need for compassion and mutual support. It’s about how we can and need to be better to one another and avoid reaching such extremes in our lives. Leaving the 9/11 Museum, I often feel a sense of optimism and a renewed perspective on the world.

The stories surrounding 9/11 are incredibly diverse and complex. Understanding the events requires looking into what led to the attacks, including the political climate and global conditions at the time. Beyond the immediate loss, there are also stories of heroism and sacrifice. For many who joined the fire department or the first responders in general, the risk of danger was part of the job, though not always fully anticipated. I've had friends in the fire department who approached their role with a sense of duty and a commitment to helping others, perhaps not fully considering the extreme risks involved. However, many didn’t fully consider the physical risks they were taking when they signed up. There’s the story of their personal bravery, but also the broader narrative of community resilience and the collective commitment to the common good and well-being.

Just as a song can evoke memories of the first time you heard it or who you were with, architecture can also trigger memories. The places we visit and the spaces we inhabit become integral to our personal and collective histories and memories. Our built environment is more than just bricks and mortar; in many ways, it defines who we are. It shapes our interactions and serves as the backdrop to our memories of one another. The World Trade Center, for example, holds a significant place in our cultural memory. It had a history before 9/11, carries the memory of that tragic day, and continues to be part of our shared experience. Each of us may connect to it in a unique way, but the memories it holds are collectively ours.

The story of 9/11 extends far beyond the basic facts of an attack on our country and the tragic loss of nearly 3,000 lives, though those details are undeniably significant. The complexity and depth of the events, including the broader context and the human stories involved, are crucial for a fuller understanding. Without the 9/11 Museum, conveying this comprehensive narrative and capturing the full scope of what happened becomes much more challenging.

Jennifer Wegner, a contributor to this story, is the Editorial Manager at Page.